Economics of Refugees : Canada Could Strike a Great Blow for Democracy

From Saturday Night, March 1939

By Gwethalyn Graham

◊ Gwethalyn Graham (1913 – 1965) was a Toronto-born writer, whose 1944 novel Earth and High Heaven was the first Canadian book to reach number one on the New York Times best-seller list. Graham won the Governor General’s Award twice, for her first novel Swiss Sonata in 1938, and for Earth and High Heaven in 1944. In the 1930s and 1940s she was a noted activist working to change Canada’s restrictive immigration policies, which barred Jewish refugees from Germany and other European countries even though they were under dire threat back home.

There are two major objections which are raised whenever admission of the Jewish refugees is discussed; the first, that so long as we have unemployed of our own we have no right to open up immigration of any sort, and the second, that the absorption of so many aliens more or less at one gulp would be impossible.

To begin with the first point, there are a good many economists who disagree with the theory that immigration increases unemployment, and their arguments are worth great consideration, since the lives of so many people depend on us.

Supposing immigration does increase unemployment, then the contrary should hold true. If our population were reduced by the number now receiving relief, this country would then be able to provide jobs for everyone. If the balance between production and consumption is more or less exact, then the optimum population of Canada is ten or eleven million, not twelve, and our present unemployment is due to over-population. No one, however, could reasonably maintain that if you have ten people, one will be on relief; if you have twenty, two will be jobless, and so on. In other words, there is no fixed ratio between then number of people and the number of jobs available; there is a variation not only between countries but between different localities within a country.

On the other hand, it is clear that each immigrant is a consumer as well as a producer, and that for every one added there is a further demand for capital equipment, as well as for such personal requirements as housing, clothing, food and transportation. If each individual spends his total earnings, consuming the equivalent of what he produces each day, then the balance between production and consumption will apparently remain largely what it was. This statement only holds good so long as the immigrant has better than average earning power, however, as it is fairly generally accepted that for the people in the lower wage groups, a large part of both capital and personal equipment is provided by the well-to-do, and by reserve capital accumulation. Anyone who doubts this has only to look at the housing problem in almost any country where it is recognized that a man supporting a family on ten or twelve dollars a week cannot pay the rent of a decent house without assistance.

On this basis there is every justification for the belief that the demand for goods created by fairly extensive immigration exceeds the quantity which the immigrants can produce. This country is not suffering from a general shortage at the moment, but rather from a depression which is at least partly due to a lack of demand for capital goods.

So far as giving jobs to our own unemployed rather than to immigrants is concerned, if those jobs are there, ready to be seized by outsiders, why haven’t our jobless men and women filled them before this? Do those jobs actually exist? They do not, as ninety-nine out of a hundred unemployed will tell you. We appear to have reached a dead end where our general condition is static. With mass immigration it would be dynamic. If the statement that such mass immigration would in all probability not only take care of itself but provide a partial solution for our already existing problems seems paradoxical, it is at least not more paradoxical than hunger on the one hand and the deliberate destruction or restriction of crops on the other.

You may say that economic theories such as those given above are all very well, but before this country undertakes to settle a large number of immigrants at one time, some more concrete proof that it can be done successfully is needed.

There is such proof in Greece.

In 1922 and 1923, one million four hundred thousand Greeks had to leave the shores of Asia Minor where they had lived for 3,000 years. They numbered more than a quarter of the total population of Greece at that time, and not even an immigration of three and a half million into Canada would provide a comparable problem, for Greece is a small, poor country.

In 1922 and 1923, one million four hundred thousand Greeks had to leave the shores of Asia Minor where they had lived for 3,000 years. They numbered more than a quarter of the total population of Greece at that time, and not even an immigration of three and a half million into Canada would provide a comparable problem, for Greece is a small, poor country.

Of those 1,400,000 refugees, possibly 200,000 had a little capital. The rest were penniless, many with nothing beyond the clothing on their backs. Most were urban shopkeepers, members of professions, grocers, waiters, servants, tailors, shoemakers, yet the majority had to be settled on the land.

By means of loans floated with the aid of the League of Nations, and grants by the Greek government itself, what M. W. Fodor describes as “the greatest involuntary migration of peoples ever recorded in the pages of history” got under way. Six hundred and fifty thousand were settled in towns, some of which already existed while most were built up overnight by the immigrants themselves. The arrival of vast numbers of refugees in previously settled communities created economic crises in the beginning, for the immigrants plunged into the enterprises for which they had been trained, whether or not such enterprises were needed. The crises abated, however, for at the same time other industries which required the establishment of retail businesses were started, and the absorption of surplus labor was accomplished over a comparatively short period.

About 150,000 families were settled on the land, some of which had been tilled, some so far untilled. They also started new industries such as the breeding of silkworms, the production of tobacco and cotton. It was found that they were more progressive and in many cases more efficient and willing to try new methods than the old, established inhabitants.

There were of course those who failed, as there are always, in any country, those who fail. The Greek refugees were in no sense homogeneous; there were many among them who spoke only Turkish, whose religion, customs, and general culture were far more alien to the Greeks than those of the German and Austrian Jews would be to us. Greece is a western country, Turkey an eastern. Many of them had to make the adjustment between the Asiatic and European culture.

The statement that the Jew is very largely what his Gentile neighbor had made him seems to be borne out by the experience of England, and pre-Hitlerist Germany and Austria. At this crucial time when false generalizations are heard on every hand, it is perhaps worth while to remember that according to modern anthropological belief, the Jew does not differ so much from the Gentiles who surround him as he does from the Jew of another country. Many of us have a kind of collective face in mind which we label “Jewish,” if we do not know the blonde, blue-eyed Jews of Vienna, and if we have not encountered a shaven-headed, keen-featured man of military bearing whom we would unhesitatingly call “Prussian,” but who turns out to be a doctor from Berlin of pure Jewish origin.

Those who will not heed the refugees’ plea for land of their own, maintaining that Jews are not farmers and never have been and never will be, usually fail to take into consideration the fact that until very recently there was almost no country where Jewish ownership of land was permitted. In spite of that, some Jews have been farmers, however, notably in the Ukraine and North Caucasus, where countless families got around the Imperial Russian laws by renting land on what was often an illegal 99-year lease system. Generation after generation tilled soil which was not and never could be their own.

The dog in the manger has never been much admired. Whether we like it or not, that is the way we look to the outside world at the moment, and so long as thousands of helpless men, women and children are suffering intolerable persecutions and abuse in Germany, or being herded like cattle from one already crowded European country to another, while we continue to slam our door and refuse them admission, there will be little reason for anyone to think better of us. Beyond certain material contributions, Canada has done little or nothing for humanity as a whole. We merely exist, harming no one, and doing no one any good either. It is a record of mediocrity.

The Nazis jeer at us, say we make a great show of equality of race and creed, and criticize them for not wanting their Jews, while in actual fact we don’t want them either. There is just enough truth in those accusations to make any honest Canadian uncomfortable, and there are many of us who feel that should Finns, or Swedes, or Norwegians have been forced to endure such atrocious suffering through no fault of their own, we, the people of Canada, would have taken some action before this. If that is the case, the implications behind it bode us no good.

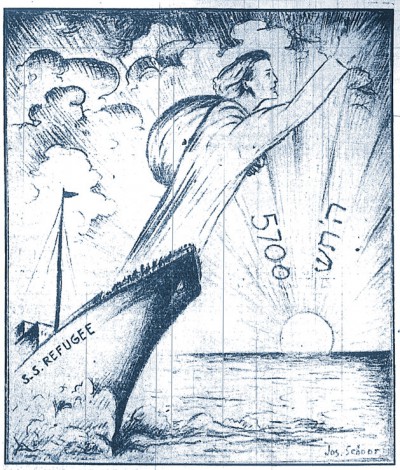

Our sympathy is of no assistance to a group of several hundred human beings huddled together on a boat midway between Austria and Czechoslovakia, unable to go either forward or back, nor to all those people waiting desolately in offices and parks and railway stations for some country to lead the way. Should that country be Canada, we would thereby strike the greatest blow for democracy this country could make, and no one can say how powerful and far-reaching an effect it might have upon the issue which now divides the world. ♦