In lieu of baseball cards, some American Orthodox boys have turned in recent decades to collecting Torah personality trading cards that feature images of revered “Gedolim” (Giants) from Moses Maimonides to Rabbi Moishe Feinstein, with lists of famous published works on the back in lieu of batting statistics. The happy invention of a Baltimore accountant, Torah Personalities cards have been available (in packs, but minus the bubble gum) since 1989. Rare cards reportedly sell for hundreds of dollars.

In lieu of baseball cards, some American Orthodox boys have turned in recent decades to collecting Torah personality trading cards that feature images of revered “Gedolim” (Giants) from Moses Maimonides to Rabbi Moishe Feinstein, with lists of famous published works on the back in lieu of batting statistics. The happy invention of a Baltimore accountant, Torah Personalities cards have been available (in packs, but minus the bubble gum) since 1989. Rare cards reportedly sell for hundreds of dollars.

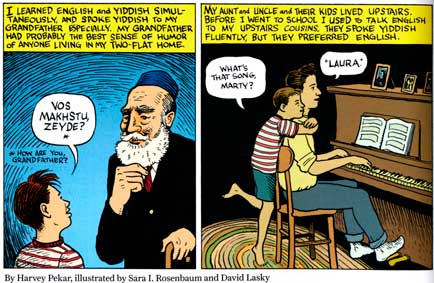

The devolution of high-minded rabbinical lore into the arena of popular American culture has a certain parallel in the recent publication of Yiddishkeit: Jewish Vernacular & The New Land (Harry N. Abrams), a collection of graphic writing about Yiddish culture edited by Harvey Pekar and Paul Buhle.

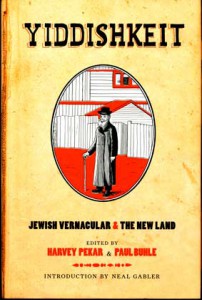

Pekar, who died in July 2010, has become a sort of “Gedolim” in his own right. A self-admitted “shlump” who led a lonely existence as a lowly file clerk in Cleveland, he teamed up with R. Crumb and other comic-book artists to transform the dross of his life into gold. Using stick figures, he wrote and drew short autobiographical pieces that the artists spun into American Splendor, a wondrously ironic and highly popular comic-book series.

Pekar, who died in July 2010, has become a sort of “Gedolim” in his own right. A self-admitted “shlump” who led a lonely existence as a lowly file clerk in Cleveland, he teamed up with R. Crumb and other comic-book artists to transform the dross of his life into gold. Using stick figures, he wrote and drew short autobiographical pieces that the artists spun into American Splendor, a wondrously ironic and highly popular comic-book series.

When the eponymous movie came out in 2003 with Paul Giametti playing Pekar, it completed the latter’s transformation from Zero to Hero and brought him a goodly measure of success and renown. In a Wikipedia entry devoted to him, Pekar is quoted as saying that American Splendor is “an autobiography written as it’s happening. The theme is about staying alive. Getting a job, finding a mate, having a place to live, finding a creative outlet.” One imagines he died more contented and fulfilled for having made a genuine mark upon the world.

Yiddishkeit, the book, is a graphic celebration of Yiddish culture that includes several major pieces by Pekar in collaboration with his talented artists. We learn that his first language was Yiddish and that, as an adult, he developed advanced tastes in Yiddish literature.

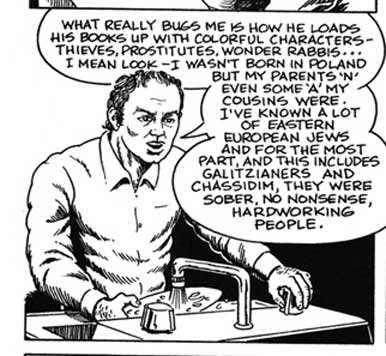

However, although finely illustrated by Dan Archer, his two pieces recounting the history of classic and modern Yiddish lit are uneven, wordy and idiosyncratic. Appearing as himself in the cartoon, Pekar complains at one point that Isaac Bashevis Singer is “so overrated it makes me sick. James Joyce never got a Nobel Prize but I.B. Singer did. Wonderful – maybe next year Harold Robbins’ll get it.” The anthology is also saddled with a 42-page script called The Essence, A Yiddish Theatre Dim Sum that, whatever its virtues on the stage, pales to blandness on the page.

However, although finely illustrated by Dan Archer, his two pieces recounting the history of classic and modern Yiddish lit are uneven, wordy and idiosyncratic. Appearing as himself in the cartoon, Pekar complains at one point that Isaac Bashevis Singer is “so overrated it makes me sick. James Joyce never got a Nobel Prize but I.B. Singer did. Wonderful – maybe next year Harold Robbins’ll get it.” The anthology is also saddled with a 42-page script called The Essence, A Yiddish Theatre Dim Sum that, whatever its virtues on the stage, pales to blandness on the page.

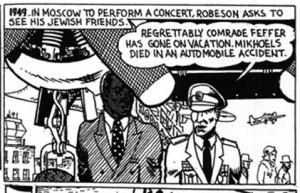

These failings aside, there are many gems here. The series of page-long cartoons by Joel Schechter and drawn by Manuel (Spain) Rodriguez are particularly fine in the way they dramatize pivotal and legendary moments in Yiddishkeit. Robeson Sings Yiddish chronicles the great American singer’s visit to Moscow in 1949 where he performed a concert in Yiddish. During his historic trip, Robeson asked the Soviet authorities if he might see his two Jewish friends, and was told one was on holiday and the other had died in an automobile accident. In truth, one had been imprisoned and the other murdered by the KGB.

Chayale Ash’s Day in Court, also by Schechter and Spain, presents the tale of the Romanian actress and troupe who were arrested in Haifa in 1948 for performing in Yiddish because the government “was afraid Yiddish would overtake Hebrew, the national language.” Ash and troupe countersued, emerged victorious and resumed their performances. Mark Twain Translated, another Schechter-Spain cartoon, dramatizes the memorable meeting of Sholem Aleichem and Mark Twain – the one being “the Jewish Mark Twain” and the other “the American Sholem Aleichem.”

Chayale Ash’s Day in Court, also by Schechter and Spain, presents the tale of the Romanian actress and troupe who were arrested in Haifa in 1948 for performing in Yiddish because the government “was afraid Yiddish would overtake Hebrew, the national language.” Ash and troupe countersued, emerged victorious and resumed their performances. Mark Twain Translated, another Schechter-Spain cartoon, dramatizes the memorable meeting of Sholem Aleichem and Mark Twain – the one being “the Jewish Mark Twain” and the other “the American Sholem Aleichem.”

In the editor’s introduction to a three-page graphic depiction of Yip Harburg’s Depression-era song Brother Can You Spare a Dime?, we learn something new about the left-leaning lyricist whose greatest contribution to popular culture may have been the lyrics in The Wizard of Oz. Evidently the word “rainbow” did not “exist in the literary original of The Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum. It was Harburg’s key addition and, right-wing critics accurately charged, implied an idyllic socialism.”

Several pieces are pleasantly drenched in nostalgia for the Yiddish New York of a century ago, from Rivington Street to Second Avenue. Coney Island, Nathaniel Buchwald’s lively and flavourful Yiddish essay from 1926 (translated by Hershl Hartman), wonderfully conveys the sights, sounds and smells of that crowded beach paradise, while Peter Kuper’s fine illustration perfectly captures its essence. And a fascinating set of cartoons from the old American Yiddish satirical journal Der Groyser Kundes (The Big Stick) seems to convey a world of information about the vanished milieu of the Yiddish theatre.

There are odes to the cinema here, too. Abraham Lincoln Polonsky, a piece about the American screenwriter of Body and Soul and Force of Evil (script by Dave Wagner, Paul Buhle, Peter Kuper; art by Kuper), is a stark and lovely depiction of the accomplished film-noir genius. An overly long depiction (12 pages) of Edgar G. Ulmer’s 1937 film Green Fields, as retold and drawn by Sharon Rudahl, at least provides the occasion for the editors to recall Ulmer’s worthy contributions to American cinema.

Although not particularly dramatically rendered, a three-page cartoon about Aaron Lansky, founder of the National Yiddish Book Center, rightfully attempts to canonize him in the pantheon of Yiddish underdogs and heroes that this book seeks to immortalize.

A peculiar mixture for sure, and some of it questionable, but there is still plenty to satisfy in this odd grab bag of Yiddishkeit. ♦

This article appeared originally in the Canadian Jewish News, June 20, 2012. © 2012